As you saw in the previous chapter, the list data type is an illusion created by a set of functions that manipulate cons cells. Common Lisp also provides functions that let you treat data structures built out of cons cells as trees, sets, and lookup tables. In this chapter I'll give you a quick tour of some of these other data structures and the functions for manipulating them. As with the list-manipulation functions, many of these functions will be useful when you start writing more complicated macros and need to manipulate Lisp code as data.

Treating structures built from cons cells as trees is just about as

natural as treating them as lists. What is a list of lists, after

all, but another way of thinking of a tree? The difference between a

function that treats a bunch of cons cells as a list and a function

that treats the same bunch of cons cells as a tree has to do with

which cons cells the functions traverse to find the values of the

list or tree. The cons cells traversed by a list function, called the

list structure, are found by starting at the first cons cell and

following CDR references until reaching a NIL. The elements

of the list are the objects referenced by the CARs of the cons

cells in the list structure. If a cons cell in the list structure has

a CAR that references another cons cell, the referenced cons

cell is considered to be the head of a list that's an element of the

outer list.1 Tree structure, on the other hand, is traversed by

following both CAR and CDR references for as long as they

point to other cons cells. The values in a tree are thus the

atomic--non-cons-cell-values referenced by either the CARs or

the CDRs of the cons cells in the tree structure.

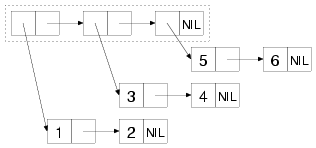

For instance, the following box-and-arrow diagram shows the cons

cells that make up the list of lists: ((1 2) (3 4) (5 6)). The

list structure includes only the three cons cells inside the dashed

box while the tree structure includes all the cons cells.

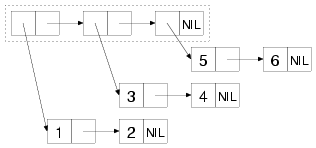

To see the difference between a list function and a tree function,

you can consider how the functions COPY-LIST and COPY-TREE

will copy this bunch of cons cells. COPY-LIST, as a list

function, copies the cons cells that make up the list structure. That

is, it makes a new cons cell corresponding to each of the cons cells

inside the dashed box. The CARs of each of these new cons cells

reference the same object as the CARs of the original cons cells

in the list structure. Thus, COPY-LIST doesn't copy the sublists

(1 2), (3 4), or (5 6), as shown in this

diagram:

COPY-TREE, on the other hand, makes a new cons cell for each of

the cons cells in the diagram and links them together in the same

structure, as shown in this diagram:

Where a cons cell in the original referenced an atomic value, the

corresponding cons cell in the copy will reference the same value.

Thus, the only objects referenced in common by the original tree and

the copy produced by COPY-TREE are the numbers 1-6, and the

symbol NIL.

Another function that walks both the CARs and the CDRs of a

tree of cons cells is TREE-EQUAL, which compares two trees,

considering them equal if the tree structure is the same shape and if

the leaves are EQL (or if they satisfy the test supplied with

the :test keyword argument).

Some other tree-centric functions are the tree analogs to the

SUBSTITUTE and NSUBSTITUTE sequence functions and their

-IF and -IF-NOT variants. The function SUBST, like

SUBSTITUTE, takes a new item, an old item, and a tree (as

opposed to a sequence), along with :key and :test

keyword arguments, and it returns a new tree with the same shape as

the original tree but with all instances of the old item replaced

with the new item. For example:

CL-USER> (subst 10 1 '(1 2 (3 2 1) ((1 1) (2 2)))) (10 2 (3 2 10) ((10 10) (2 2)))

SUBST-IF is analogous to SUBSTITUTE-IF. Instead of an old

item, it takes a one-argument function--the function is called with

each atomic value in the tree, and whenever it returns true, the

position in the new tree is filled with the new value.

SUBST-IF-NOT is the same except the values where the test

returns NIL are replaced. NSUBST, NSUBST-IF, and

NSUBST-IF-NOT are the recycling versions of the SUBST

functions. As with most other recycling functions, you should use

these functions only as drop-in replacements for their nondestructive

counterparts in situations where you know there's no danger of

modifying a shared structure. In particular, you must continue to

save the return value of these functions since you have no guarantee

that the result will be EQ to the original tree.2

Sets can also be implemented in terms of cons cells. In fact, you can treat any list as a set--Common Lisp provides several functions for performing set-theoretic operations on lists. However, you should bear in mind that because of the way lists are structured, these operations get less and less efficient the bigger the sets get.

That said, using the built-in set functions makes it easy to write set-manipulation code. And for small sets they may well be more efficient than the alternatives. If profiling shows you that these functions are a performance bottleneck in your code, you can always replace the lists with sets built on top of hash tables or bit vectors.

To build up a set, you can use the function ADJOIN. ADJOIN

takes an item and a list representing a set and returns a list

representing the set containing the item and all the items in the

original set. To determine whether the item is present, it must scan

the list; if the item isn't found, ADJOIN creates a new cons

cell holding the item and pointing to the original list and returns

it. Otherwise, it returns the original list.

ADJOIN also takes :key and :test keyword

arguments, which are used when determining whether the item is

present in the original list. Like CONS, ADJOIN has no

effect on the original list--if you want to modify a particular list,

you need to assign the value returned by ADJOIN to the place

where the list came from. The modify macro PUSHNEW does this for

you automatically.

CL-USER> (defparameter *set* ()) *SET* CL-USER> (adjoin 1 *set*) (1) CL-USER> *set* NIL CL-USER> (setf *set* (adjoin 1 *set*)) (1) CL-USER> (pushnew 2 *set*) (2 1) CL-USER> *set* (2 1) CL-USER> (pushnew 2 *set*) (2 1)

You can test whether a given item is in a set with MEMBER and

the related functions MEMBER-IF and MEMBER-IF-NOT. These

functions are similar to the sequence functions FIND,

FIND-IF, and FIND-IF-NOT except they can be used only with

lists. And instead of returning the item when it's present, they

return the cons cell containing the item--in other words, the sublist

starting with the desired item. When the desired item isn't present

in the list, all three functions return NIL.

The remaining set-theoretic functions provide bulk operations:

INTERSECTION, UNION, SET-DIFFERENCE, and

SET-EXCLUSIVE-OR. Each of these functions takes two lists and

:key and :test keyword arguments and returns a new list

representing the set resulting from performing the appropriate

set-theoretic operation on the two lists: INTERSECTION returns a

list containing all the elements found in both arguments. UNION

returns a list containing one instance of each unique element from

the two arguments.3 SET-DIFFERENCE returns a list

containing all the elements from the first argument that don't appear

in the second argument. And SET-EXCLUSIVE-OR returns a list

containing those elements appearing in only one or the other of the

two argument lists but not in both. Each of these functions also has

a recycling counterpart whose name is the same except with an N

prefix.

Finally, the function SUBSETP takes two lists and the usual

:key and :test keyword arguments and returns true if

the first list is a subset of the second--if every element in the

first list is also present in the second list. The order of the

elements in the lists doesn't matter.

CL-USER> (subsetp '(3 2 1) '(1 2 3 4)) T CL-USER> (subsetp '(1 2 3 4) '(3 2 1)) NIL

In addition to trees and sets, you can build tables that map keys to values out of cons cells. Two flavors of cons-based lookup tables are commonly used, both of which I've mentioned in passing in previous chapters. They're association lists, also called alists, and property lists, also known as plists. While you wouldn't use either alists or plists for large tables--for that you'd use a hash table--it's worth knowing how to work with them both because for small tables they can be more efficient than hash tables and because they have some useful properties of their own.

An alist is a data structure that maps keys to values and also supports reverse lookups, finding the key when given a value. Alists also support adding key/value mappings that shadow existing mappings in such a way that the shadowing mapping can later be removed and the original mappings exposed again.

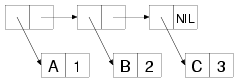

Under the covers, an alist is essentially a list whose elements are

themselves cons cells. Each element can be thought of as a key/value

pair with the key in the cons cell's CAR and the value in the

CDR. For instance, the following is a box-and-arrow diagram of

an alist mapping the symbol A to the number 1, B to 2,

and C to 3:

Unless the value in the CDR is a list, cons cells representing

the key/value pairs will be dotted pairs in s-expression

notation. The alist diagramed in the previous figure, for instance,

is printed like this:

((A . 1) (B . 2) (C . 3))

The main lookup function for alists is ASSOC, which takes a key

and an alist and returns the first cons cell whose CAR matches

the key or NIL if no match is found.

CL-USER> (assoc 'a '((a . 1) (b . 2) (c . 3))) (A . 1) CL-USER> (assoc 'c '((a . 1) (b . 2) (c . 3))) (C . 3) CL-USER> (assoc 'd '((a . 1) (b . 2) (c . 3))) NIL

To get the value corresponding to a given key, you simply pass the

result of ASSOC to CDR.

CL-USER> (cdr (assoc 'a '((a . 1) (b . 2) (c . 3)))) 1

By default the key given is compared to the keys in the alist using

EQL, but you can change that with the standard combination of

:key and :test keyword arguments. For instance, if you

wanted to use string keys, you might write this:

CL-USER> (assoc "a" '(("a" . 1) ("b" . 2) ("c" . 3)) :test #'string=)

("a" . 1)Without specifying :test to be STRING=, that ASSOC

would probably return NIL because two strings with the same

contents aren't necessarily EQL.

CL-USER> (assoc "a" '(("a" . 1) ("b" . 2) ("c" . 3)))

NILBecause ASSOC searches the list by scanning from the front of

the list, one key/value pair in an alist can shadow other pairs with

the same key later in the list.

CL-USER> (assoc 'a '((a . 10) (a . 1) (b . 2) (c . 3))) (A . 10)

You can add a pair to the front of an alist with CONS like this:

(cons (cons 'new-key 'new-value) alist)

However, as a convenience, Common Lisp provides the function

ACONS, which lets you write this:

(acons 'new-key 'new-value alist)

Like CONS, ACONS is a function and thus can't modify the

place holding the alist it's passed. If you want to modify an alist,

you need to write either this:

(setf alist (acons 'new-key 'new-value alist))

or this:

(push (cons 'new-key 'new-value) alist)

Obviously, the time it takes to search an alist with ASSOC is a

function of how deep in the list the matching pair is found. In the

worst case, determining that no pair matches requires ASSOC to

scan every element of the alist. However, since the basic mechanism

for alists is so lightweight, for small tables an alist can

outperform a hash table. Also, alists give you more flexibility in

how you do the lookup. I already mentioned that ASSOC takes

:key and :test keyword arguments. When those don't suit

your needs, you may be able to use the ASSOC-IF and

ASSOC-IF-NOT functions, which return the first key/value pair

whose CAR satisfies (or not, in the case of ASSOC-IF-NOT)

the test function passed in the place of a specific item. And three

functions--RASSOC, RASSOC-IF, and RASSOC-IF-NOT--work

just like the corresponding ASSOC functions except they use the

value in the CDR of each element as the key, performing a

reverse lookup.

The function COPY-ALIST is similar to COPY-TREE except,

instead of copying the whole tree structure, it copies only the cons

cells that make up the list structure, plus the cons cells directly

referenced from the CARs of those cells. In other words, the

original alist and the copy will both contain the same objects as the

keys and values, even if those keys or values happen to be made up of

cons cells.

Finally, you can build an alist from two separate lists of keys and

values with the function PAIRLIS. The resulting alist may

contain the pairs either in the same order as the original lists or

in reverse order. For example, you may get this result:

CL-USER> (pairlis '(a b c) '(1 2 3)) ((C . 3) (B . 2) (A . 1))

Or you could just as well get this:

CL-USER> (pairlis '(a b c) '(1 2 3)) ((A . 1) (B . 2) (C . 3))

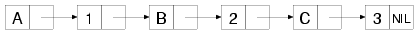

The other kind of lookup table is the property list, or plist, which

you used to represent the rows in the database in Chapter 3.

Structurally a plist is just a regular list with the keys and values

as alternating values. For instance, a plist mapping A,

B, and C, to 1, 2, and 3 is simply the list (A 1

B 2 C 3). In boxes-and-arrows form, it looks like this:

However, plists are less flexible than alists. In fact, plists

support only one fundamental lookup operation, the function

GETF, which takes a plist and a key and returns the associated

value or NIL if the key isn't found. GETF also takes an

optional third argument, which will be returned in place of NIL

if the key isn't found.

Unlike ASSOC, which uses EQL as its default test and allows

a different test function to be supplied with a :test

argument, GETF always uses EQ to test whether the provided

key matches the keys in the plist. Consequently, you should never use

numbers or characters as keys in a plist; as you saw in Chapter 4,

the behavior of EQ for those types is essentially undefined.

Practically speaking, the keys in a plist are almost always symbols,

which makes sense since plists were first invented to implement

symbolic "properties," arbitrary mappings between names and values.

You can use SETF with GETF to set the value associated with

a given key. SETF also treats GETF a bit specially in that

the first argument to GETF is treated as the place to modify.

Thus, you can use SETF of GETF to add a new key/value pair

to an existing plist.

CL-USER> (defparameter *plist* ()) *PLIST* CL-USER> *plist* NIL CL-USER> (setf (getf *plist* :a) 1) 1 CL-USER> *plist* (:A 1) CL-USER> (setf (getf *plist* :a) 2) 2 CL-USER> *plist* (:A 2)

To remove a key/value pair from a plist, you use the macro REMF,

which sets the place given as its first argument to a plist

containing all the key/value pairs except the one specified. It

returns true if the given key was actually found.

CL-USER> (remf *plist* :a) T CL-USER> *plist* NIL

Like GETF, REMF always uses EQ to compare the given

key to the keys in the plist.

Since plists are often used in situations where you want to extract

several properties from the same plist, Common Lisp provides a

function, GET-PROPERTIES, that makes it more efficient to extract

multiple values from a single plist. It takes a plist and a list of

keys to search for and returns, as multiple values, the first key

found, the corresponding value, and the head of the list starting with

the found key. This allows you to process a property list, extracting

the desired properties, without continually rescanning from the front

of the list. For instance, the following function efficiently

processes--using the hypothetical function

process-property--all the key/value pairs in a plist for a

given list of keys:

(defun process-properties (plist keys)

(loop while plist do

(multiple-value-bind (key value tail) (get-properties plist keys)

(when key (process-property key value))

(setf plist (cddr tail)))))The last special thing about plists is the relationship they have

with symbols: every symbol object has an associated plist that can be

used to store information about the symbol. The plist can be obtained

via the function SYMBOL-PLIST. However, you rarely care about

the whole plist; more often you'll use the functions GET, which

takes a symbol and a key and is shorthand for a GETF of the same

key in the symbols SYMBOL-PLIST.

(get 'symbol 'key) === (getf (symbol-plist 'symbol) 'key)

Like GETF, GET is SETFable, so you can attach

arbitrary information to a symbol like this:

(setf (get 'some-symbol 'my-key) "information")

To remove a property from a symbol's plist, you can use either

REMF of SYMBOL-PLIST or the convenience function

REMPROP.4

(remprop 'symbol 'key) === (remf (symbol-plist 'symbol key))

Being able to attach arbitrary information to names is quite handy when doing any kind of symbolic programming. For instance, one of the macros you'll write in Chapter 24 will attach information to names that other instances of the same macros will extract and use when generating their expansions.

One last tool for slicing and dicing lists that I need to cover since

you'll need it in later chapters is the DESTRUCTURING-BIND

macro. This macro provides a way to destructure arbitrary lists,

similar to the way macro parameter lists can take apart their

argument list. The basic skeleton of a DESTRUCTURING-BIND is as

follows:

(destructuring-bind (parameter*) list body-form*)

The parameter list can include any of the types of parameters

supported in macro parameter lists such as &optional,

&rest, and &key parameters.5 And, as in macro parameter lists, any parameter can be

replaced with a nested destructuring parameter list, which takes

apart the list that would otherwise have been bound to the replaced

parameter. The list form is evaluated once and should return a

list, which is then destructured and the appropriate values are bound

to the variables in the parameter list. Then the body-forms are

evaluated in order with those bindings in effect. Some simple

examples follow:

(destructuring-bind (x y z) (list 1 2 3) (list :x x :y y :z z)) ==> (:X 1 :Y 2 :Z 3) (destructuring-bind (x y z) (list 1 (list 2 20) 3) (list :x x :y y :z z)) ==> (:X 1 :Y (2 20) :Z 3) (destructuring-bind (x (y1 y2) z) (list 1 (list 2 20) 3) (list :x x :y1 y1 :y2 y2 :z z)) ==> (:X 1 :Y1 2 :Y2 20 :Z 3) (destructuring-bind (x (y1 &optional y2) z) (list 1 (list 2 20) 3) (list :x x :y1 y1 :y2 y2 :z z)) ==> (:X 1 :Y1 2 :Y2 20 :Z 3) (destructuring-bind (x (y1 &optional y2) z) (list 1 (list 2) 3) (list :x x :y1 y1 :y2 y2 :z z)) ==> (:X 1 :Y1 2 :Y2 NIL :Z 3) (destructuring-bind (&key x y z) (list :x 1 :y 2 :z 3) (list :x x :y y :z z)) ==> (:X 1 :Y 2 :Z 3) (destructuring-bind (&key x y z) (list :z 1 :y 2 :x 3) (list :x x :y y :z z)) ==> (:X 3 :Y 2 :Z 1)

One kind of parameter you can use with DESTRUCTURING-BIND and

also in macro parameter lists, though I didn't mention it in Chapter

8, is a &whole parameter. If specified, it must be the first

parameter in a parameter list, and it's bound to the whole list

form.6 After a &whole parameter, other parameters

can appear as usual and will extract specific parts of the list just

as they would if the &whole parameter weren't there. An example

of using &whole with DESTRUCTURING-BIND looks like this:

(destructuring-bind (&whole whole &key x y z) (list :z 1 :y 2 :x 3) (list :x x :y y :z z :whole whole)) ==> (:X 3 :Y 2 :Z 1 :WHOLE (:Z 1 :Y 2 :X 3))

You'll use a &whole parameter in one of the macros that's part

of the HTML generation library you'll develop in Chapter 31. However,

I have a few more topics to cover before you can get to that. After

two chapters on the rather Lispy topic of cons cells, you can now

turn to the more prosaic matter of how to deal with files and

filenames.

1It's possible to build a chain of cons cells where

the CDR of the last cons cell isn't NIL but some other

atom. This is called a dotted list because the last cons is a

dotted pair.

2It may

seem that the NSUBST family of functions can and in fact does

modify the tree in place. However, there's one edge case: when the

"tree" passed is, in fact, an atom, it can't be modified in place, so

the result of NSUBST will be a different object than the

argument: (nsubst 'x 'y 'y) X.

3UNION takes only one element from each

list, but if either list contains duplicate elements, the result may

also contain duplicates.

4It's also possible to directly SETF

SYMBOL-PLIST. However, that's a bad idea, as different code may have

added different properties to the symbol's plist for different

reasons. If one piece of code clobbers the symbol's whole plist, it

may break other code that added its own properties to the plist.

5Macro parameter lists do

support one parameter type, &environment parameters, which

DESTRUCTURING-BIND doesn't. However, I didn't discuss that

parameter type in Chapter 8, and you don't need to worry about it now

either.

6When a &whole parameter is used in a macro parameter

list, the form it's bound to is the whole macro form, including the

name of the macro.